Terms of Care, Part 4: A Digital Health Blueprint

How to reform digital health infrastructure so health tech can flourish

Healthcare is aspirational. It attempts to treat the sick, mend the broken, and keep society functioning and healthy. Balancing the personnel, training, resources, and time is a massive task. All healthcare systems have problems.

There aren’t enough doctors. There aren’t enough beds, shots, and the hospital is too far away. Care is too expensive; insurance and billing are too hard to navigate. You can’t get an appointment for months, can’t get the drugs you need, can’t find a human to explain what’s really going on with your stomach ache…

The design of the system, or rather, the policies and programs that regulate it, shape the problems that system faces. One example; there were no increases to subsidies for residency programs (the last step in training physicians) by the federal government from 1997 to 2020. Today, physician shortages are estimated to exceed 10,000, and patients wait months for appointments.

These are the Terms of Care within healthcare systems.

Throughout this series I’ve tried to make the case that digital health infrastructure has the greatest potential of different reform platforms to reshape American’s experience of, and trust in the healthcare system. Potential for an accessible, personalized, interconnected healthcare system; easier to navigate for providers and patients and administrators. Potential to rethink the terms of care.

Defining terms

So what is digital health infrastructure? By definition; computerized organizational structures needed for the functioning of the healthcare system.

While researching this series, I identified 5 domains of digital infrastructure in healthcare, based on the needs of those working within the healthcare system, and the people it serves: Governance, Usability, Data Security & Access, Interoperability & Data Storage, and Payments.

In this final part, I’ll cover what the current landscape looks like in each of these domains, and what it should look like if we are to meet aspirational visions of a 21st century healthcare system.

Governance

Since 2009 (HITECH Act), health IT vendors are regulated by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC). If you’re an EHR developer, you’ll submit your platform to testing through the ONC Health IT Certification Program[7,8]. While this program is voluntary, it is the only certification program which ensures adherence to HIPAA and confers eligibility to federal and state incentive programs for EHR development[7,8]. Not to mention, Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements may be jeopardized if a provider doesn’t comply with HIPAA.

Not all health IT products are EHR systems. The ONC certification program also publishes a Certified Health IT Products List (CHPL)[7], which includes basically all commercially available health products through their use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs).

APIs are a set of protocols which determine how different software components interact with each other. One of the classic examples is a waiter in a restaurant. The restaurant doesn’t let customers go into the kitchen and cook their own food. Instead, they interact with a waiter (API), the waiter relays their order to the kitchen (data pool, server, other software), then brings food back to the customer (end-user)[3].

What’s the process like?

Developers choose an ONC-Authorized Testing Laboratory (ATL)

These labs are designated to run conformance tests against ONC-defined technical criteria (like API standards).Testing Phase

Vendors must pass a battery of tests for each certification criterion they’re seeking. For example, if they want certification for "e-Prescribing" or "Patient Access API," they have to pass that targeted test with predefined sample data.ONC-Authorized Certification Body (ACB) Review

Once the ATL confirms successful testing, an ACB reviews documentation, test results, and attestations before issuing certification.Public Listing

Certified products are published on the CHPL, including version numbers and active/inactive status.

For a legacy vendor, the process typically takes 3–6 months. For new entrants or products previously flagged for compliance issues, it can take upwards of 15 months.

Again, virtually all health IT products pass through this ONC Certification program. This helps by establishing a baseline of interoperability, security, data formats, and safety features. But, it hurts more.

New entrants (especially small startups or open-source platforms) often lack the money, or legal support to effectively navigate certification, gatekeeping innovation. Plus, once certified, vendors can be hesitant to make changes that could trigger re-certification. This can stall innovation, and has real-world consequences.

During COVID-19, providers and startups struggled to deploy rapid-response tools (like pop-up vaccine scheduling) due to fears that rapid deployment might trigger re-certification processes.

This exemplifies Jen Pahlka’s critique in “Recoding America”: bureaucracies often incentivize compliance over outcomes. The ONC certification program is meant to operationalize health tech, ensure patient access, and encourage interoperability. But it’s increasingly strangling innovation, and hasn’t meaningfully improved user, or patient experiences.

Most of the proceeding recommendations will involve reforms to the ONC Health IT Certification Program.

Usability

Usability is how easily and effectively clinicians, patients, caregivers, and administrators interact with a digital health system. It encompasses user interface, navigation, and cognitive load. Here, we’re talking mostly about how end-users interact with various APIs.

Current State

Studies show that for every hour of direct patient care, physicians may spend nearly two hours on the EHR[4]. Patient access to health information is inconsistent, 3 in 5 patients in 2022 were offered access to their records, and accessed them[5]. 1 in 3 of those patients reported being offered more than 1 portal by different clinical services[5].

Only 2% of patients reported using digital apps to consolidate their health records and information[5]. Finally, poor user-interfaces and the absence of multilingual support and digital literacy design elements disproportionately harm elderly users, and non-native speakers.

Recommendations

Instead of all-or-nothing certification, ONC should let systems opt into a sandbox track where they provide real-world metrics (task time, error rates, bounce rates) under observational review. This would encourage and enable iterative improvement over multi-year cycles, with certification credit for testing and refining based on user feedback.

Task time, and error rate metrics can be used to create public scorecards (like FDA device recalls) tracking usability issues. This new, dynamic and competitive environment would incentivize Health IT vendors to compete over real-world outcomes, not compliance and contracts.

Data Security & Access

Security means protecting patient data from unauthorized access, corruption, or loss. Access is the entry point to digital care: identity, authentication, connectivity, and interface

Current State

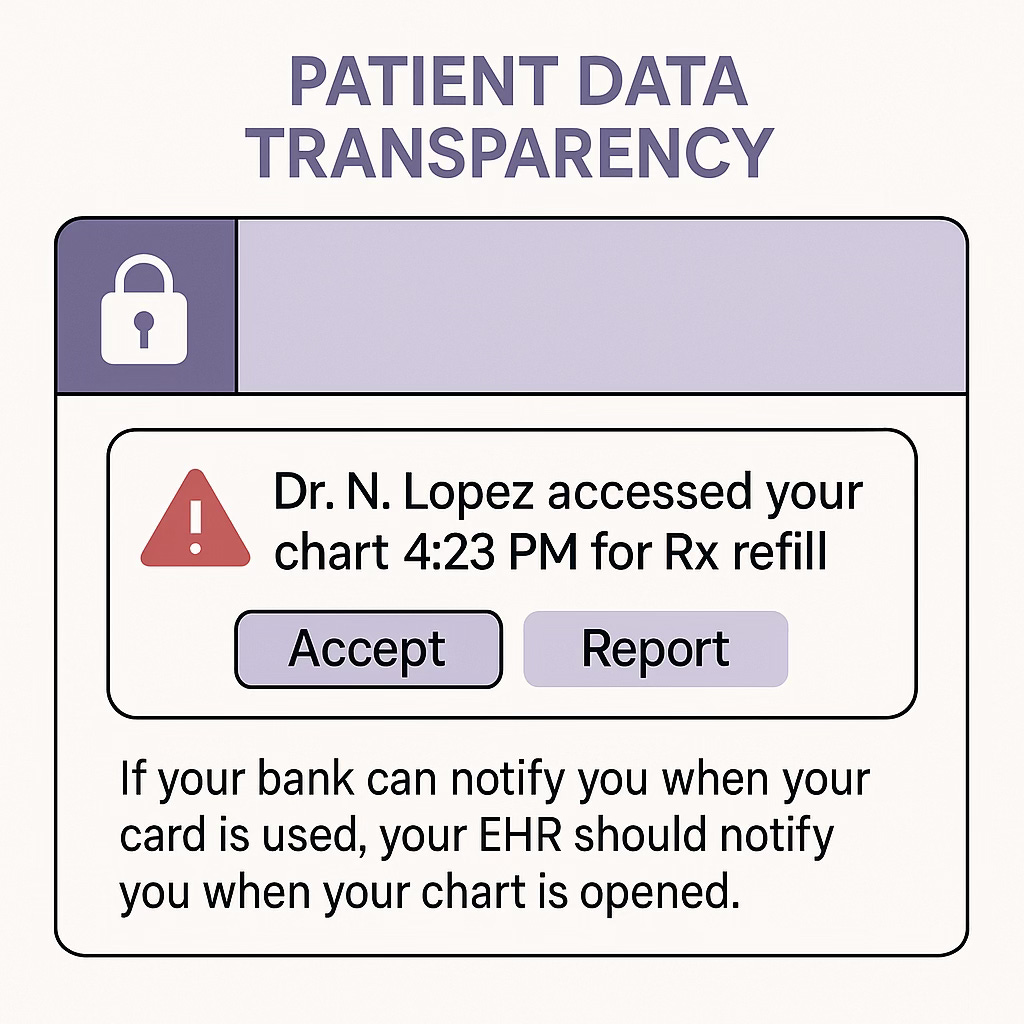

Health systems focus on HIPAA compliance, but still suffer major breaches. Over 133 million health records were breached in 2023 alone. Most access controls are role-based (RBAC), but patients rarely know who accessed their data or why. Certified systems must meet basic audit logging requirements, but there’s no mandate to make those logs visible, user-friendly, or patient-facing.

Security is regulated as a fixed technical spec, not a living, situational process. ONC certification verifies that systems can log access and protect per HIPAA, but it doesn’t reward platforms that innovate around transparency, granularity, or patient governance. Identity verification can be a big problem in healthcare too. But, the ONC’s most recent innovation has been standardizing the format of how patient addresses are stored from APIs[10]… this is unacceptable.

Recommendations

Instead of hard-coding roles, we should support purpose-driven (treatment, billing, public health) access rules with real-time patient oversight. Patients could set permissions, exceptions, and expiration timers. Roles should still be attributed to users, which should be visible and auditable for workflow and safety.

Transparency builds trust. Patient-centered APIs should allow certified systems to show patients who accessed their data, when, and for what purpose (not just via downloadable CSVs, but clean dashboards). This could look like real-time alerts when new devices or unfamiliar institutions access their record.

For safety, we’d need to verify it’s really the patient making decisions. Rather than wait for a federal patient ID (which HIPAA prevents), we should support decentralized identity frameworks (DIDs), and/or multi-factor authentication.

Multi-factor authentication systems are common and secure (Amazon, Netflix, education platforms, etc.). DIDs may be further away, but health tech companies are working on it.

Finally, we should support place-based policy; local grants to support components that are proven effective in diverse communities (e.g., portals that work with voice input, or that support Indigenous languages, low health literacy). Dynamic accessibility features would allow patients and clinicians to restructure care with a platform rather than working around it.

We should stop treating privacy as a static perimeter and start designing systems for shared, contextual control. Certification should reward transparent, dynamic governance; the most secure platforms, with the most accessible user-experience.

Interoperability & Data Storage

In 2018, ONC released their first draft of the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA), which aimed to establish a nationwide framework for health information exchange. Participation is still voluntary.

Data storage is primed to become a problem. The amount of data generated in healthcare has been increasing by 47% each year[13], but we may be able to kill two birds with one stone here.

Current State

Change in data management is always difficult, and TEFCA asks for a new level of trust in external data sources. Additionally, TEFCA demands technical adjustments in how EHR systems query, retrieve, and integrate outside records into clinical workflows.

What TEFCA is really asking for is compliance with their published regulations about interoperability. This mostly involves also using a specific set of API servers, while choosing from the CHBP list of certified APIs.

Recommendations

One advantage of using external data sources is that it reduces the amount of data storage needed at any one institution. So, by rolling TEFCA participation into the ONC certification program, we make meaningful progress towards interoperability, and alleviate some future data storage problems.

Additionally, we should create dynamic incentives for helpful and innovative usage of TEFCA data. I don’t want more box-checking APIs that could share an updated medication list across primary, specialty, and pharmacy care. I want new tools that will notify my endocrinologist and me when my insulin prescription is about to expire, allow them to update it with one-click, and update my pharmacy, automatically.

Payments

EHR design is, in many ways, shaped not by what patients need, but by what billing rules require. That’s a product of both ONC certification incentives and payment architectures.

Current State

Clinical documentation is often a thin veil over billing compliance. Value-based payment models exist, and have been in the news recently, but EHRs rarely support the changes in workflow those models demand. Preventive care, social needs screening, or patient engagement are harder to translate into billable activity. As policy interest moves toward value, real-world systems lag because vendors aren’t incentivized to build tools that don’t pay.

Technologically, we haven’t embraced automatic payments either. In Australia, instantaneous payments from public and private payers happen every day, via electronic claims processing.

Recommendations

Many of the value-based payment models being discussed were innovations made by CMS. We should be creating CMS innovation model APIs which translate care models into billable codes, and codes into auditable data. Notable examples in these spaces include CMS’s Direct Contracting and the ACO REACH model. If there are barriers to using alternative payment models, there will be less participation.

Most medical billing services exist outside of EHRs. Some existing services can automate payments for sets of common ICD codes[14]. We need to incentivize API development which bridges automatic billing and EHR. If common codes can be automated, we could free up billing services to create new pathways to bill for alternative payment models. Reliable billing codes make it easier for teams to provide services they may be afraid would otherwise go unpaid.

A New Reform

We know what to build. We’ve named the parts. We’ve seen it work in other nations. The U.S. doesn’t lack digital tools. It lacks an infrastructure to put it all together. A cohesive vision to improve healthcare.

The ONC Certification Program should evolve from an all-or-nothing gatekeeper to a dynamic performance scaffold; a structure that encourages innovation, and rewards developers that offer value to improve patient-centered outcomes, not just compliance. These reforms have the potential to unleash health tech, at scale, in this decade. The potential to rewrite our terms of care.

The first patent for seatbelts was actually awarded in 1885 to Edward J Claghorn. But, it wasn’t until 1968 that the federal government (NHTSA) required seatbelts be installed in new cars, and it wasn’t until 1984 that passengers were required to use them. The invention is credited with saving lives, but the policy made it so.

Digital health infrastructure isn’t just about software. It’s about accessibility, trust, and rebuilding a healthcare system for patients. We’ve invented the seatbelts. Now, we need to make sure they’re used.

Sources:

[1] EHR Report 2022—Software Path

[3] Application programming interface (API)

[5] ONC Report: Individuals’ Access and Use of Patient Portals and Smartphone Health Apps, 2022

[7] ONC Health IT Certification Program (2024)

[8] What Is The ONC Certification Program and Why Should it Matter to You?

[9] ASTP: Health IT Certificate Program—Real World Testing

[10] ONC Project US@

[11] Decentralized Identifiers, a primer

[12] TEFCA promise

Great read, Chris. You're right. I've had health records breached and I realized that I'm so desensitized at this point, that I didn't think about what the hacker was after or why. Nor did the health care provider offer an explanation.

You have me thinking ...