Terms of Care, Part 3: Bits, Bytes, and Bills... and Bills and Bills

Infrastructure and trust in digital health systems

Trust and Taxes

In September 2024, The Commonwealth Fund published an analysis comparing health systems of 10 developed nations in five key areas: access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health outcomes[9]. If your diagnosis of the American healthcare system calls out the moral failing in numbers of uninsured patients, or systemic mistreatment of women and minority groups— you’re correct, America ranked dead last in access, and next to last in equity. If your measure of success is a longer and healthier life— dead last. If you’re familiar with the industry, and blame the administrative bloat and waste— you’re correct too—the U.S. ranks second-to-last in efficiency and spends the most[9].

But, if you think Medicare-for-all, or “concepts-of-a-plan” will fix all of these problems — I have bad news.

Mary’s $100

Meet Mary, the median American; female, 39 years-old, she makes a little over $40,000/year, and pays into a private health insurance plan through her employer[3]. She pays just under $1800 for health insurance, her employer pays around $9000 into the plan per her enrollment[1].

For every $100 paid into Mary’s private health insurance plan—

$25 goes towards administrative costs

$22 goes to hospitals for inpatient care

$20 goes towards doctors and outpatient services

$15 for buying prescription drugs

$5 goes towards digital infrastructure

$3 goes towards public health and preventative care

$10 goes towards an assortment of other services (medical equipment, mental health, rehabilitation services, etc)[5,6,7,8]

Now consider a median Finnish citizen, who pays into a national tax-funded system. For every $100, just $3 goes to administrative costs, and $5 in digital infrastructure funds a unified record (KanTa) where patients can read visit summaries, prescription lists and consent forms for themselves[11]. In South Korea, the digital infrastructure allotment goes towards creating a mobile app which consolidates records across all providers[15]. “In Australia, electronic claims processing ensures instantaneous payments from public and private payers[9].” Singaporeans can request prescription refills and pay medical bills through a one-stop “HealthHub”[10].

When Mary goes to the doctor or picks up a prescription she’ll still pay out-of-pocket towards her deductible, her medical records are still scattered across different apps and EHRs, she’ll have to find that email with her portal login to view lab results, and she’ll still spend half-an-hour on hold with billing. When something goes wrong—a billing dispute, a duplicate test, a specialist who can’t find the referral—

Mary is the one left navigating the chaos.

Trust is dead. Not just between Mary and her doctor, but between insurance companies and doctors, doctors and admin, on and on and on.

Visibility

In the U.S., patient access to medical records remains deeply inconsistent. The 2016 CURES act legally mandates health information systems provide patients access to medical information—upon request.

So, you likely have access to a portal—if your provider offers one, and if you remember the login. Otherwise, you could submit written requests to your clinic’s Health Information Manager, if you can find their information online. Or, perhaps you could submit a HIPAA request through another portal. But, this might be the first you’re hearing of the CURES act, and the thought of requesting and finding all that information sounds time intensive, and not ultimately worth it.

Healthcare systems should remember you. This should be automatic. When a specialist hasn’t seen your primary care notes, or when a medication list is out of date, the system treats you like a stranger. It asks you to retell your story. Again and again

Dividends and Penalties

This inaccessibility has real costs. A 2018 survey found that one in five U.S. adults with a chronic illness reported having to re-explain their medical history to a new provider because records weren’t available[18].

These aren’t just paperwork delays—they’re lapses in care.

A 2016 study in the Journal of Patient Safety estimated that medical errors—many caused by fragmented information—could be the third leading cause of death in the U.S.[19].

Countries like Denmark alleviate these problems not because they have better doctors, but because they’ve built better digital infrastructure. Every Danish citizen has a Central Personal Register (CPR) number, linking their entire medical history across hospitals, pharmacies, and providers via sundhed.dk[10]. In Portugal, the SNS 24 portal gives every resident a single, unified digital entry point[10].

When people can see what the system sees, they’re more likely to trust the system. Visibility is a form of accountability—a form of continuity. Continuity reduces risk. It also builds trust. When your doctor walks in already knowing your history, the conversation can begin with care.

The State of U.S. Digital Infrastructure

So, where are we exactly? The U.S. healthcare system is almost entirely digitized—at least in theory. The HITECH Act, passed in 2009, offered billions in incentives to promote EHR adoption. It succeeded in getting nearly every hospital and clinic onto some form of EHR. Today, over 96% of non-federal hospitals use certified Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems. However, meaningful use criteria focused on adoption, not connection. Hospitals digitized — but exist within closed-loop networks.

The government formalized interoperability standards for health information in 2012 with Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) (HL7 was available before 2012, but FHIR reorganized prior recommendations into a resource package). Then the CURES act banned information blocking by EHR vendors and health information networks with fines up to $1million for restricting patient access.

There haven’t been many lawsuits made under the CURES act, but a recent ruling against EHR vendor ‘PointClickCare’ may change that tide[20].

TEFCA

The other big piece of legislation we need to cover is TEFCA—the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement. First launched in 2022, TEFCA is designed to build a “network of networks” to connect health information exchanges (HIEs), hospitals, and clinics through a common set of data-sharing standards. Its implementation is led by The Sequoia Project, a nonprofit coordinating entity tasked with getting vendors and providers to play nicely.

But TEFCA is still voluntary. And many major EHR vendors—Epic, Cerner (Oracle), Meditech, athenahealth—participate while maintaining proprietary systems that will require custom integration or extra fees to link up.

Patients remain stuck in limbo, and have yet to see real benefits from TEFCA, or the CURES act.

The government has offered both carrots and sticks to solve interoperability problems. What it hasn’t done is innovate.

Data: the House of Straw

And then there’s data storage and security. Personalized health solutions—from genomics to microbiome kits—promise more customized care. Wearables—like smartwatches, continuous glucose monitors, and sleep trackers—have exploded in popularity.

But the infrastructure to store, access, and securely share this data with clinicians is immature.

Interoperability doesn’t have to mean just sharing your vaccine records—it could involve your entire health picture—Apple Watch to supplements—neighborhood air-quality to blood panels—primary care to a personalized plan helping you meet your health goals.

The amount of data generated in healthcare has been increasing by 47% each year[21]. Most systems rely on a mix of local servers, private cloud contracts, and vendor-tied storage. HIPAA sets rules for privacy, and those rules get violated—probably more often than you’d feel comfortable with[22].

Solutions in data storage and security rely on technological innovations, many of which we may discuss in future articles. But for now, data storage seems like a problem of secondary importance for the platforms which support clinical workflows. Data security is a box vendors need to check to make sure they don’t get sued.

Why It Matters

Designing a digital ecosystem which allows interoperability and accessibility requires us to think about all these problems—consumer feedback, clinical decision-making, administrative compliance, and data safety[23]—simultaneously, like one big interdisciplinary mountain.

Trust is essential for people’s experience of the healthcare system, and accountable digital infrastructure is how we build it.

The countries that have invested in digital public infrastructure aren’t just more efficient. They’re more trustworthy. And that trust pays dividends.

It’s a stronger relationship between citizens and the system that serves them. It’s what enables high vaccine uptake. It’s what drives better adherence to care plans. There’s pride in a healthy society.

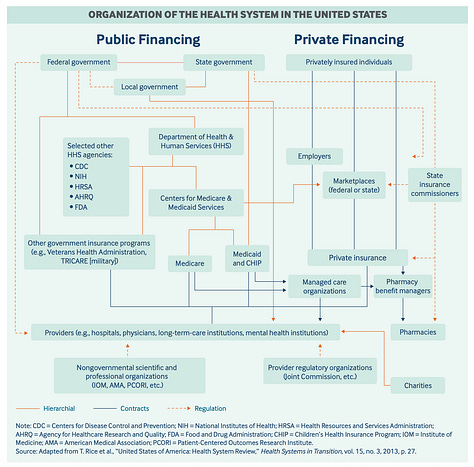

American healthcare has a privatization problem. I’m not saying that private insurance or hospitals are the problem. America actually ranked second in care process (having features and attributes associated with high quality care)[9]. But private companies lack the multidisciplinary organization—and incentives—to build public infrastructure.

Private equity did not build the interstate highway system, doesn’t get clean water to your faucet, and doesn’t deliver mail to rural areas. This needs to be a centralized effort. I want patient-owned health records, housed securely and encrypted with role-based access controls.

I want to go to my doctor, and feel like they’re talking to me, my life, my data.

—

In the final part of this series, I’ll dive deeper into what solutions for digital infrastructure could look like in America, how the current landscape is making progress, and what it all means for Americans.

Sources Cited:

[1] KFF 2024 Employer Health Benefits Survey, Section 1: Cost of Health Insurance

[2] KFF 2024 Employer Health Benefits Survey, Section 7: Employee Cost Sharing

[3] US Census Bureau

[4] CMS National Health Expenditure Projections 2023-2032

[5] AHA: The Cost of Caring – Challenges facing America’s Hospitals in 2025

[7] Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker: National Health Spending Explorer (updated 2023)

[8] Commonwealth Fund: High U.S. Health Care Spending: Where Is It All Going?

[10] TCF: 2020 International Profiles of Health Systems

[11] Internation Trade Administration: Healthcare Resource Guide - Finland

[12] OECD – Finland Profile - State of Health

[13] TCF: Medical Debt – 2023 survey

[14] South Korea: Health system at a glance

[15] South Korea’s My HealthWay: A “digital highway” of personal health records…

[17] Understanding the cost of implementing an EHR system

[18] TCF 2018: Experience of people with serious illnesses

[19] Johns Hopkins study suggests medical errors are third-leading cause of death in U.S.

[20] CURES act violation

[21] AHA: Leveraging Data for Health Care Innovation

[22] HIPAA Violations

Interesting read. I'm looking forward to your proposed solutions. It seems difficult to order the whole pie when each slice is being hoarded like a golden goose with immense lobbying power.